The exhibition explores different narratives, historical and present, about Black hair through the works of Nakeya Brown, Shani Crowe, Marius Dansou, Meschac Gaba, Romuald Hazoumè, Taiye Idahor, Favour Jonathan, Murielle Kabile, Alassane Koné, Althea Murphy-Price, J. D 'Okhai Ojeikere, Anya Paintsil, Ngozi Ajah Schommers and Ana Silva, to highlight the cultural heritage and spirituality associated with it.

Pre-colonial Africa has often been referenced as a starting period for explorations of Black hair and the myriad of complexities attached to it. Often referenced as an identifier, in some instances, it was a way to distinguish a person’s age, religion, rank, marital status, and even family groups. The different textures many people had, also had an influence on practices of care for hair. Braiding emerged as a cultural practice, becoming a time of bonding and community between women. Although many socio-historical narratives have focused on women, there is also evidence of well-defined hairstyles among men, such as the braids worn by Wolof men going off to war. Hair was seen as a form of protection and a means of staying connected to ancestors.

The Atlantic slave trade was a tragic turning point that also marked the history of Black hair, as enslaved Africans were forcibly shaved, stripping them of their identity, dignity and spiritual connection. This loss was profound, reflecting the erasure of cultural heritage perpetrated by oppressors.

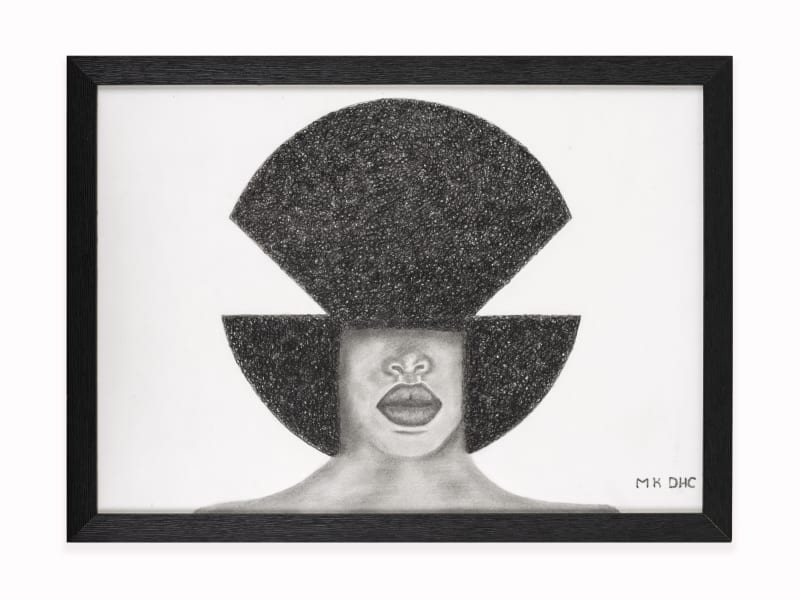

While hair can be considered a form of non-verbal communication by some, there are disparate ongoing conversations about the politicisation of Black hair. The first natural hair movement began in the 1960s, with the “Black is Beautiful” movement, which was about embracing Black skin, facial features, and Black hair. Wearing the Afro was the first step in saying “I am Black, and I am proud”.

The resurgence of the natural hair movement in the early 2000s has exposed implicit messages in the perception of Black hair highlighting its cultural acceptance or rejection by non-Black people in the mainstream and the private spheres. Through its commercial influence, with the proliferation of natural hair products in shops and countless content creators sharing daily tips on natural hair care and styling, this movement has played an important role in reshaping interpretations of Black hair. By centring Black people and their hair, emphasising the stylistic diversity of hairstyles and offering a new reading of their representation, the Natural Hair movement has impacted a cultural shift with an increasing number of Black women wearing their natural hair not only as an expression of Black pride but also as an extension of themselves.

For a long time, the message was actively inculcated that straightened hair was necessary for participation in the social hierarchy, particularly pertaining to business and politics. It has also largely been thought to embody a standard of beauty that neglects Black identity and naturalness. The media and society glorify Black women with long, straight or wavy hair, while shorter, kinkier, and nappier hair is disagreeable.

Recently, Michelle Obama explained that she had insisted on having her hair straightened throughout her husband's presidential term. She felt that the American people were “just getting used to” having their first Black family in the White House and were “not yet ready” to accept her with her natural hair. I personally had to deal with this societal pressure to conform to Western beauty standards. During my school years in South Africa, I was prohibited from wearing natural hair or locks, leading my mother to chemically straighten my hair to make it more “manageable” and “presentable” according to my school's standards.

This discrimination continues. In 2020, a retail store in South African published a racist advertisement describing Black hair as dull, dry and frizzy, while calling White people’s hair fine, normal and flat. In 2023, a Black Texas high school student served more than two weeks of in-school suspensions for wearing twisted locs to school on the grounds that “his dreadlocks fall below his eyebrows and earlobes and are a violation of the district dress code”. This reflects a generational trend of perceiving Black hair as ‘difficult’ or ‘untidy’ and in need of alteration and highlights the criticism of specific hairstyles worn by Black people.

Accepting alterity and changing mentalities is a long process that will also require legislative reforms. Some government initiatives are working to end racialised hair discrimination. In 2022, the CROWN Act (CROWN stands for “Creating a Respectful and Open World For Natural Hair”) was adopted by some American states. In France, a bill to recognise and punish hair discrimination is currently being considered by the Senate.